You wake up parched, constantly reaching for water, but no matter how much you drink, that desperate thirst never goes away. Your brain screams “dehydrated!” but your body tells a different story – one that millions don’t recognize as diabetes insipidus, a rare condition that hijacks your body’s water regulation system.

This guide is for anyone experiencing unexplained excessive thirst, frequent urination, or mysterious dehydration symptoms that don’t match typical causes. It’s also essential reading for family members trying to understand why their loved one drinks gallons of water daily yet still feels desperately thirsty.

We’ll uncover why diabetes insipidus tricks your brain into thinking you’re dying of thirst when you’re actually drowning in water. You’ll discover the four distinct types of this condition and learn to spot the early warning signs that doctors often miss. We’ll also walk through the diagnostic maze and explore treatment options that can finally give you relief from this exhausting cycle of thirst and urination.

Understanding the Core Differences Between Diabetes Insipidus and Diabetes Mellitus

Recognizing the fundamental distinctions in underlying mechanisms

The two conditions couldn’t be more different when you look at what’s actually happening inside your body. Diabetes mellitus revolves around blood sugar problems – your body either can’t make enough insulin or can’t use it properly, causing glucose to build up in your bloodstream. Think of it like having a broken key that won’t unlock your cells to let sugar in for energy.

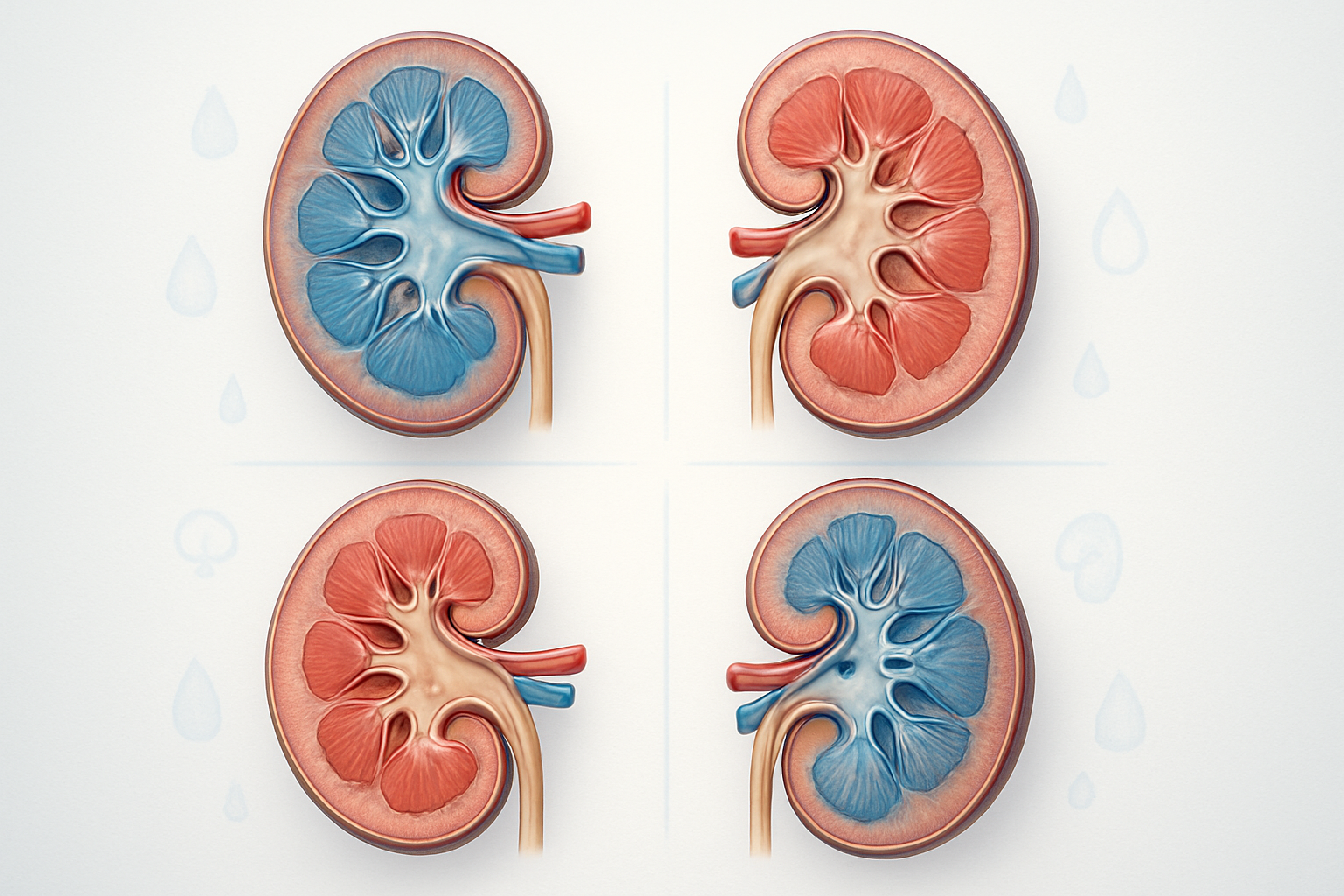

Diabetes insipidus operates on a completely different system. Your kidneys suddenly forget how to hold onto water because of problems with a hormone called antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also known as vasopressin. This hormone normally tells your kidneys to reabsorb water and concentrate your urine. When this system breaks down, your kidneys let massive amounts of water slip through, leaving you constantly thirsty and running to the bathroom.

The water regulation system involves your hypothalamus (the brain’s control center) producing ADH, which then gets stored and released by your pituitary gland. When this delicate communication breaks down anywhere along the chain, your body loses its ability to conserve water effectively. Meanwhile, diabetes mellitus affects how your pancreas produces insulin or how your cells respond to it – two entirely separate bodily systems that rarely overlap.

Identifying key symptom variations between the two conditions

While both conditions make you incredibly thirsty, the reasons and accompanying symptoms tell very different stories. People with diabetes mellitus experience what doctors call the “three P’s” – polydipsia (excessive thirst), polyuria (frequent urination), and polyphagia (excessive hunger). They might also deal with blurred vision, slow-healing cuts, tingling in hands and feet, and unexplained weight changes.

Diabetes insipidus primarily shows up as extreme thirst and producing ridiculous amounts of clear, dilute urine – we’re talking 3 to 20 liters per day. The thirst feels different too; it’s an urgent, desperate need for water that nothing else will satisfy. You won’t find the hunger, vision problems, or nerve issues that come with diabetes mellitus.

| Diabetes Mellitus | Diabetes Insipidus |

|---|---|

| Excessive hunger | No increased hunger |

| High blood sugar | Normal blood sugar |

| Dark, concentrated urine (if dehydrated) | Clear, watery urine |

| Sweet-smelling breath | Normal breath |

| Fatigue from high blood sugar | Fatigue from dehydration |

| Gradual onset often | Can be sudden onset |

People with diabetes insipidus often describe feeling like they’re constantly playing catch-up with their fluid intake, while those with diabetes mellitus struggle more with energy levels and blood sugar management.

Understanding why the shared name creates common confusion

The shared “diabetes” name comes from an ancient Greek word meaning “to pass through,” referring to excessive urination that both conditions cause. Back in ancient times, doctors had limited ways to distinguish between different diseases, so they grouped conditions by obvious symptoms rather than underlying causes.

This naming convention has created decades of confusion. When someone says they have diabetes insipidus, people immediately think about blood sugar, insulin, and dietary restrictions. Family members start worrying about carbohydrates and glucose monitoring when the real concern should be fluid balance and electrolyte management.

The confusion gets worse because both conditions can lead to serious complications if left untreated, but the treatments are completely different. Diabetes mellitus requires blood sugar management through diet, medication, or insulin therapy. Diabetes insipidus needs hormone replacement therapy or medications that help your kidneys hold onto water better.

Medical professionals sometimes contribute to the confusion by not explaining the fundamental differences clearly enough. Many people leave their doctor’s office thinking they have a “rare type of diabetes” without understanding that diabetes insipidus has virtually nothing in common with the diabetes that affects millions of people worldwide. This misunderstanding can delay proper treatment and create unnecessary anxiety about complications that don’t actually apply to their condition.

Discovering the Four Main Types of Diabetes Insipidus

Central diabetes insipidus and its brain-related causes

Central diabetes insipidus happens when your brain’s control center for water regulation goes haywire. The problem starts in your hypothalamus, a small but mighty part of your brain that produces a hormone called vasopressin (also known as ADH). This hormone tells your kidneys how much water to hold onto and how much to get rid of through urine.

When your hypothalamus gets damaged or doesn’t work right, it can’t make enough vasopressin. Without this crucial hormone, your kidneys lose their instructions and start dumping massive amounts of water from your body. You end up peeing constantly and feeling desperately thirsty.

Several things can mess up your hypothalamus:

- Head injuries from car accidents, falls, or sports injuries

- Brain tumors that press on or damage the hypothalamus

- Infections like meningitis or encephalitis that attack brain tissue

- Genetic mutations you’re born with that affect hormone production

- Surgery complications during brain or pituitary operations

- Autoimmune disorders where your immune system attacks healthy brain cells

Sometimes doctors can’t figure out what caused the damage – this gets labeled as “idiopathic” central diabetes insipidus. The scary part? Your brain might look completely normal on scans, but the hormone-producing cells have been quietly destroyed.

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and kidney dysfunction

Your kidneys might get the message from your brain loud and clear, but they’re not listening. That’s nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in a nutshell – your brain produces plenty of vasopressin, but your kidneys have become deaf to its instructions.

The problem lies in your kidney cells’ receptors and water channels. These tiny cellular doorways normally respond to vasopressin by opening up to let water back into your bloodstream instead of sending it out as urine. When these receptors break down or the water channels malfunction, water just keeps flowing out no matter how much your brain screams “STOP!”

Genetic forms can show up from birth:

- X-linked nephrogenic DI affects mostly boys and causes severe symptoms from infancy

- Autosomal recessive and dominant forms can appear at any age

Acquired causes develop over time:

- Chronic kidney disease from diabetes, high blood pressure, or other conditions

- Medications like lithium (used for bipolar disorder) that damage kidney cells

- Electrolyte imbalances, especially low potassium or high calcium levels

- Kidney infections or inflammation that scars the filtering units

Lithium deserves special mention because it’s one of the most common culprits. Long-term use can permanently damage the kidney’s ability to respond to vasopressin, even after stopping the medication.

Gestational diabetes insipidus during pregnancy

Pregnancy brings a perfect storm of hormonal changes that can trigger diabetes insipidus. Your body becomes a hormone factory working overtime, and sometimes the assembly line gets mixed up.

During pregnancy, your placenta produces an enzyme called vasopressinase. This enzyme’s job is to break down vasopressin, but sometimes it goes overboard and destroys too much of the hormone. Your brain tries to keep up by making more vasopressin, but the placenta’s enzyme works faster than your brain can produce the hormone.

Risk factors include:

- Multiple pregnancies (twins, triplets) with larger placentas producing more enzyme

- Liver problems that can’t clear the excess enzyme from your blood

- Previous history of gestational diabetes insipidus in earlier pregnancies

- HELLP syndrome or severe preeclampsia affecting liver function

The condition typically shows up in the third trimester when placental hormone production peaks. You’ll notice the classic signs – excessive urination and unquenchable thirst – but they might get brushed off as normal pregnancy symptoms.

The good news? Gestational diabetes insipidus usually resolves completely within a few weeks after delivery once the placenta is gone and hormone levels return to normal.

Primary polydipsia and excessive water intake patterns

Primary polydipsia isn’t technically diabetes insipidus, but it creates identical symptoms and often gets confused with the real thing. Your kidneys and brain work perfectly fine – the problem is that you’re drinking way too much water for reasons that have nothing to do with actual thirst.

Psychiatric polydipsia often affects people with mental health conditions:

- Schizophrenia patients may develop compulsive water drinking

- Severe anxiety can trigger excessive fluid intake as a coping mechanism

- Some psychiatric medications increase thirst or dry mouth, leading to overconsumption

Habitual polydipsia develops from lifestyle patterns:

- Athletes who’ve been told to “stay hydrated” but take it too far

- People following extreme detox or cleansing diets

- Those who mistake every minor discomfort for dehydration

- Individuals with eating disorders using water to feel full

The tricky part is that drinking excessive amounts of water actually washes out your natural vasopressin and changes your kidney’s sensitivity to the hormone. Your body adapts to the flood of incoming water by becoming less efficient at concentrating urine, creating a vicious cycle where you need to keep drinking more water to feel normal.

Breaking this cycle requires careful medical supervision because suddenly stopping excessive water intake can be dangerous if your body has adapted to the high fluid levels.

Recognizing Early Warning Signs and Symptoms

Identifying Excessive Urination Patterns and Frequency

People with diabetes insipidus experience dramatically increased urine production, often producing 3-20 liters daily compared to the normal 1-2 liters. This isn’t just frequent bathroom trips – it’s an overwhelming flood of dilute, colorless urine that disrupts every aspect of daily life.

The urination pattern typically remains consistent throughout the day, unlike other conditions where frequency might increase at certain times. You might find yourself rushing to the bathroom every 30-60 minutes, producing large volumes each time. The urine appears almost clear, like water, because your kidneys can’t concentrate it properly.

Track your bathroom visits for a few days – if you’re going more than 10 times daily with substantial volume each time, this warrants medical attention. The volume matters as much as frequency; small, frequent urinations suggest different conditions entirely.

Understanding Uncontrollable Thirst and Fluid Cravings

The thirst associated with diabetes insipidus feels different from normal thirst. It’s an intense, nagging sensation that drinking water barely touches. You might consume 3-20 liters of fluid daily, yet still feel parched within minutes of drinking.

This thirst often drives people to prefer cold drinks or ice water, and they may develop specific fluid preferences. Some describe it as feeling like they’re perpetually dehydrated despite drinking constantly. The thirst-urination cycle becomes relentless – drink, urinate, repeat, with little relief.

Unlike regular thirst that subsides after drinking, this persists regardless of fluid intake. You might wake up multiple times nightly specifically to drink water, not just to urinate.

Recognizing Dehydration Risks and Electrolyte Imbalances

Despite constant fluid consumption, dehydration remains a serious risk because the body loses water faster than it can be replaced. Warning signs include:

- Physical symptoms: Dry mouth, sunken eyes, decreased skin elasticity

- Mental changes: Confusion, difficulty concentrating, irritability

- Electrolyte disruption: Muscle cramps, weakness, irregular heartbeat

The rapid water loss can dilute essential minerals like sodium and potassium, creating dangerous imbalances. Children and elderly individuals face higher risks because their bodies handle fluid loss differently.

Monitor your urine color – even with excessive urination, very pale yellow indicates adequate hydration. Clear urine suggests overhydration, while darker colors signal dehydration despite high fluid intake.

Spotting Sleep Disruption from Frequent Nighttime Urination

Nocturia – nighttime urination – becomes a major quality-of-life issue. Most people wake up 3-6 times nightly to urinate, completely fragmenting sleep patterns. This isn’t just inconvenient; it’s exhausting and affects daytime functioning.

The disruption creates a cascade of problems:

- Chronic fatigue and daytime sleepiness

- Difficulty concentrating at work or school

- Mood changes and irritability

- Relationship strain from constant sleep interruption

Parents might notice children wetting the bed after being dry for years, or older adults might experience new-onset incontinence. The urge to urinate often comes suddenly and intensely, making it difficult to “hold it” until reaching a bathroom.

Sleep quality deteriorates significantly, leading to daytime exhaustion that compounds the other symptoms. Many people report feeling like they never get truly restful sleep because of constant interruptions.

Exploring Root Causes and Risk Factors

Brain injuries and pituitary gland disorders

The brain’s command center for water regulation sits in a tiny area called the hypothalamus, which works closely with the pituitary gland. When something goes wrong in this delicate partnership, diabetes insipidus can develop.

Head trauma stands as one of the most common culprits. Car accidents, falls, sports injuries, or any significant blow to the head can damage the hypothalamus or disrupt the connection between the brain and pituitary gland. Even seemingly minor concussions sometimes trigger this condition weeks or months later.

Brain tumors present another major risk factor. Both cancerous and non-cancerous growths can press against the hypothalamus or pituitary gland, interfering with normal hormone production. Craniopharyngiomas, pituitary adenomas, and meningiomas are particularly problematic because they grow in areas critical for water balance.

Surgical procedures involving the brain or pituitary region carry inherent risks. Neurosurgery to remove tumors, repair aneurysms, or address other brain conditions can accidentally damage the delicate structures responsible for ADH production. The risk varies depending on the surgery’s location and complexity.

Infections affecting the brain pose additional threats. Meningitis, encephalitis, and other inflammatory conditions can damage the hypothalamus or pituitary gland. These infections create swelling and inflammation that disrupts normal hormone pathways, sometimes permanently.

Other brain-related causes include strokes affecting the hypothalamus, inflammatory conditions like sarcoidosis, and autoimmune disorders that attack the pituitary gland.

Genetic factors and inherited conditions

Family history plays a significant role in some cases of diabetes insipidus. Several genetic mutations can disrupt the normal production or function of antidiuretic hormone, leading to inherited forms of the condition.

Familial neurohypophyseal diabetes insipidus represents the most well-known genetic variant. This autosomal dominant condition means only one parent needs to carry the faulty gene for a child to potentially develop the disorder. The mutation affects the AVP gene, which provides instructions for making ADH.

The symptoms often don’t appear immediately at birth. Instead, they typically emerge during childhood or adolescence as the brain’s ability to produce functional ADH gradually declines. This delayed onset can make diagnosis challenging, especially when family history isn’t clearly established.

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus also has genetic components. Mutations in the AVPR2 gene or AQP2 gene can cause the kidneys to become resistant to ADH, even when the hormone is produced normally. The AVPR2 mutation follows an X-linked inheritance pattern, meaning it primarily affects males, while AQP2 mutations can affect both sexes equally.

Some rare genetic syndromes include diabetes insipidus as part of a broader constellation of symptoms. Wolfram syndrome, also called DIDMOAD syndrome, combines diabetes insipidus with diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, and deafness. This progressive condition affects multiple organ systems.

CHARGE syndrome, another genetic disorder, can include diabetes insipidus along with heart defects, growth delays, and various physical abnormalities.

Medications and treatments that trigger the condition

Certain medications and medical treatments can interfere with ADH production or function, triggering temporary or permanent diabetes insipidus. Understanding these pharmaceutical triggers helps patients and doctors make informed treatment decisions.

Lithium, commonly prescribed for bipolar disorder, ranks among the most notorious culprits. Long-term lithium use can make the kidneys less responsive to ADH, essentially creating nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. The risk increases with higher doses and longer treatment duration. Regular monitoring becomes essential for patients on lithium therapy.

Some antibiotics and antiviral medications can disrupt normal kidney function. Amphotericin B, used to treat serious fungal infections, sometimes causes temporary kidney problems that interfere with water regulation. Certain antiviral drugs used for HIV treatment have similar effects.

Chemotherapy drugs present another category of concern. Some cancer treatments can damage the kidneys or affect hormone production. Cisplatin and other platinum-based chemotherapy agents are particularly problematic, sometimes causing permanent kidney damage that affects water balance.

Contrast dyes used during medical imaging procedures occasionally trigger kidney problems in susceptible individuals. While most people handle these substances without issues, those with existing kidney problems face higher risks.

Diuretics, ironically, can sometimes contribute to the problem. While these “water pills” are designed to help the body eliminate excess fluid, they can occasionally disrupt normal kidney function in ways that mimic diabetes insipidus.

Anesthesia and surgical procedures, especially those involving the brain or kidney area, carry potential risks for developing temporary diabetes insipidus. Most cases resolve once the body recovers from the procedure.

Navigating Diagnostic Tests and Medical Evaluations

Water Deprivation Tests and Their Importance

The water deprivation test stands as the gold standard for diagnosing diabetes insipidus, though it sounds more intimidating than it actually is. During this controlled medical procedure, you’ll stop drinking fluids for 8-12 hours while doctors monitor your body’s response. Your medical team will track your urine output, concentration levels, and blood sodium throughout the process.

What makes this test so revealing is how your kidneys react to fluid restriction. People with diabetes insipidus continue producing large volumes of dilute urine even when dehydrated, while those with normal kidney function concentrate their urine to conserve water. The test gets stopped immediately if you show signs of severe dehydration or if your sodium levels climb too high.

Doctors often combine this with a synthetic hormone injection called desmopressin. If your urine becomes more concentrated after receiving this hormone, you likely have central diabetes insipidus. No response suggests nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, where your kidneys can’t respond to the hormone properly.

The procedure requires hospital supervision because dehydration can become dangerous quickly. Medical staff will weigh you regularly and check your vital signs every hour. Most people find the hardest part is simply feeling thirsty, but knowing the test provides crucial diagnostic information makes the temporary discomfort worthwhile.

Blood and Urine Analysis for Hormone Levels

Laboratory tests reveal the chemical story behind your symptoms through detailed analysis of blood and urine samples. Your doctor will measure antidiuretic hormone (ADH) levels, also called vasopressin, which normally helps your kidneys retain water. People with central diabetes insipidus show abnormally low ADH levels, while those with the nephrogenic form may have normal or elevated levels.

Blood tests also check your sodium concentration, which typically runs high in diabetes insipidus due to excessive water loss. Your doctor will examine your blood osmolality – essentially how concentrated your blood is – alongside urine osmolality. The contrast between these two measurements provides valuable diagnostic clues.

| Test Type | Normal Range | DI Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Sodium | 135-145 mEq/L | Often >145 mEq/L |

| Blood Osmolality | 280-295 mOsm/kg | Usually >295 mOsm/kg |

| Urine Osmolality | 300-900 mOsm/kg | Often <300 mOsm/kg |

| ADH Level | 1-5 pg/mL | Variable based on type |

Twenty-four-hour urine collections help doctors calculate your exact fluid output and loss patterns. These comprehensive measurements paint a complete picture of how your body handles fluid balance, making diagnosis more accurate than relying on symptoms alone.

MRI Scans for Detecting Brain Abnormalities

Magnetic resonance imaging gives doctors a detailed view inside your brain, specifically targeting the pituitary gland where ADH production occurs. The scan can reveal tumors, infections, injuries, or structural abnormalities that might be disrupting hormone production. Advanced MRI techniques can even visualize the posterior pituitary’s “bright spot” – a normal finding that often disappears in central diabetes insipidus.

Brain imaging becomes especially important when symptoms develop suddenly or are accompanied by headaches, vision changes, or other neurological symptoms. The scan can detect pituitary adenomas, craniopharyngiomas, or damage from head trauma that might explain your condition.

Your radiologist will pay special attention to the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, the critical brain region controlling hormone production. Sometimes MRI reveals unexpected findings like empty sella syndrome, where the pituitary gland appears flattened or absent. The procedure takes about 45 minutes and requires you to lie still while the machine creates detailed cross-sectional images.

Contrast dye may be used to highlight specific brain structures, though this adds minimal risk for most people. The scan provides crucial information for treatment planning, especially if surgery or targeted therapy might be needed to address underlying causes.

Genetic Testing for Hereditary Forms

Genetic analysis has become increasingly important as researchers identify specific gene mutations causing inherited diabetes insipidus. Several genes can be involved, including AVPR2, AQP2, and AVP genes, each affecting different parts of the water regulation system. Testing becomes particularly valuable when multiple family members show similar symptoms or when the condition appears in childhood.

The process involves a simple blood draw or saliva sample sent to specialized laboratories for DNA analysis. Results typically take 2-4 weeks and can identify specific mutations responsible for the condition. This information helps predict disease progression, guide treatment choices, and provide genetic counseling for family planning decisions.

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus shows different inheritance patterns depending on the specific gene involved. X-linked forms primarily affect males, while autosomal recessive types require mutations from both parents. Understanding your genetic profile helps doctors choose the most effective treatments and monitor for potential complications.

Genetic testing also benefits family members who might carry mutations without showing symptoms yet. Early identification allows for preventive monitoring and prompt treatment if the condition develops. The information proves especially valuable for parents planning future pregnancies or adult children concerned about passing the condition to their offspring.

Effective Treatment Options and Management Strategies

Hormone Replacement Therapy with Desmopressin

Desmopressin stands as the gold standard treatment for most cases of diabetes insipidus, essentially replacing the antidiuretic hormone your body isn’t producing or responding to properly. This synthetic hormone comes in several forms – nasal sprays, tablets, and injections – giving you flexibility in how you manage your condition.

The nasal spray version works fastest, typically reducing excessive urination within an hour. Many people prefer this method because it’s convenient and mimics how your body naturally releases ADH. Tablets take longer to kick in but offer more consistent results throughout the day. Your doctor will start with a low dose and gradually adjust based on how your body responds.

Finding the right dosage requires patience. Too little desmopressin means you’ll still deal with frequent urination and thirst. Too much can lead to water retention and dangerously low sodium levels. Most people need adjustments during the first few weeks as their medical team monitors urine output and blood sodium levels.

Side effects are generally mild but worth watching for. Headaches, nausea, and mild fluid retention can occur, especially when starting treatment. Some people experience nasal congestion with the spray form, which might affect absorption and require switching to tablets.

Dietary Modifications and Fluid Intake Guidelines

Managing fluid intake becomes a delicate balancing act when you have diabetes insipidus. Your natural instinct might be to drink whenever you feel thirsty, but this approach can actually work against your treatment, especially if you’re taking desmopressin.

The key is drinking enough to prevent dehydration without overloading your system. Most doctors recommend spreading fluid intake throughout the day rather than gulping large amounts at once. Keep a water bottle nearby, but sip regularly instead of chugging when thirst hits hard.

Timing matters when you’re on medication. If you take desmopressin, drinking too much water can dilute your blood sodium to dangerous levels. Your medical team will provide specific guidelines, but generally, you’ll want to limit fluids for a few hours after taking your medication.

Certain foods can help maintain proper hydration levels. Fresh fruits like watermelon and oranges contribute to fluid intake while providing essential electrolytes. Avoid excessive caffeine and alcohol, as both can interfere with your body’s water balance and potentially reduce the effectiveness of your treatment.

Salt intake deserves special attention. While you shouldn’t go overboard, completely restricting sodium isn’t usually necessary unless your doctor specifically recommends it. Some people find that maintaining adequate salt levels helps their body respond better to treatment.

Medication Adjustments for Underlying Conditions

When other health conditions contribute to your diabetes insipidus, treating these root causes becomes part of your overall management strategy. This multi-layered approach often produces better results than focusing solely on hormone replacement.

Blood pressure medications sometimes need tweaking since some types can affect kidney function and fluid balance. Diuretics, commonly called “water pills,” might need adjustment or replacement with alternatives that don’t interfere with your ADH treatment. Your cardiologist and endocrinologist will work together to find medications that manage your blood pressure without worsening your diabetes insipidus symptoms.

Psychiatric medications present unique challenges. Lithium, commonly used for bipolar disorder, can cause nephrogenic diabetes insipidus by making your kidneys resistant to ADH. If you can’t stop lithium, your doctor might add medications like amiloride or hydrochlorothiazide to help your kidneys respond better to treatment.

Anti-seizure medications and some antibiotics can also affect kidney function. Regular monitoring becomes crucial when you’re taking multiple medications. Blood tests every few months help catch any interactions before they become serious problems.

Pain medications, particularly those containing NSAIDs like ibuprofen, can reduce kidney function over time. Your doctor might recommend acetaminophen as a safer alternative for managing chronic pain.

Lifestyle Changes for Optimal Symptom Control

Creating a routine that supports your treatment makes daily life much more manageable. Sleep patterns deserve special attention since many people with diabetes insipidus struggle with nighttime symptoms. Keeping a small amount of water by your bedside prevents dehydration without encouraging excessive drinking during the night.

Exercise requires some planning but remains completely possible. Intense workouts can increase fluid needs, so time your activities carefully around medication doses. Swimming and water aerobics often work well because you’re less likely to become overheated and extremely thirsty.

Travel planning becomes more involved but shouldn’t limit your adventures. Carry extra medication in case of delays, and research medical facilities at your destination. Time zone changes can affect medication timing, so work with your doctor to create an adjustment plan before long trips.

Workplace accommodations might be necessary, especially jobs with limited bathroom access. Most employers are understanding when you explain the medical necessity. Having access to fluids and restroom breaks isn’t just comfort – it’s health maintenance.

Stress management plays a bigger role than many people realize. High stress levels can worsen symptoms and make it harder to maintain consistent medication routines. Regular exercise, adequate sleep, and stress-reduction techniques like meditation can improve your overall symptom control.

Building a support network helps tremendously. Family members and close friends should understand your condition and know how to recognize signs of serious complications like severe dehydration or water intoxication.

Living Successfully with Diabetes Insipidus

Daily Management Routines and Planning Strategies

Creating a structured daily routine becomes your lifeline when managing diabetes insipidus. Start each day by checking your fluid intake schedule and keeping water bottles within arm’s reach wherever you go. Many people find success using smartphone apps to track their water consumption and medication timing, setting gentle reminders every few hours.

Your bathroom breaks will likely increase to 10-20 times daily, so plan your schedule around this reality. Map out bathroom locations at work, during errands, and on regular routes. Keep a small cooler bag with extra water and your medications, treating it like a portable safety kit.

Sleep quality often suffers due to frequent nighttime urination, but you can minimize disruptions by limiting fluids two hours before bed (while ensuring adequate hydration throughout the day). Place a large water bottle by your bedside and consider a small nightlight to navigate safely during dark bathroom trips.

Meal planning requires extra attention since certain foods affect your fluid balance. Salty or high-sodium foods increase thirst, while water-rich fruits and vegetables help maintain hydration. Keep hydrating snacks like watermelon, cucumber, or soup readily available.

Emergency Preparedness and Dehydration Prevention

Dehydration emergencies can escalate quickly with diabetes insipidus, making preparation absolutely critical. Create an emergency kit containing at least three days’ worth of medications, electrolyte supplements, and contact information for your healthcare team. Store duplicate kits in your car, workplace, and with trusted family members.

Learn to recognize your personal dehydration warning signs early. These might include dizziness when standing, decreased skin elasticity, dark yellow urine, or unusual fatigue. Don’t wait until symptoms worsen – address them immediately with increased fluid intake and rest.

Develop relationships with local pharmacies and ensure they have your prescription information on file. During natural disasters or emergencies when regular medical care isn’t accessible, knowing multiple locations where you can obtain medications becomes invaluable.

Weather extremes demand extra vigilance. Hot weather accelerates fluid loss, while air conditioning and heating systems can be surprisingly dehydrating. Cold weather might mask thirst signals, leading to unconscious dehydration. Adjust your fluid intake based on environmental conditions and activity levels.

Workplace and Travel Considerations

Professional environments require honest communication with supervisors about your medical needs. Request a desk near restroom facilities and negotiate flexible break schedules when possible. Keep extra water bottles, snacks, and medications in your workspace, treating them as essential work supplies rather than conveniences.

Air travel presents unique challenges due to cabin pressure, dry air, and limited bathroom access. Drink water consistently throughout flights, avoid alcohol and excess caffeine, and inform flight attendants about your medical condition. Aisle seats become non-negotiable for easy bathroom access.

Road trips need careful planning with frequent stops every hour or two. Research rest areas and clean facilities along your route. Pack more water and medications than you think necessary – traffic delays or unexpected detours can extend travel time significantly.

International travel requires additional preparation, including carrying medical documentation in local languages, researching healthcare facilities at your destination, and ensuring adequate medication supplies that account for time zone changes and potential delays.

Building Support Networks and Communication Strategies

Your support network starts with educating family members and close friends about diabetes insipidus. Many people confuse it with diabetes mellitus, so clear explanations help them understand your specific needs and potential emergencies. Teach trusted individuals to recognize dehydration symptoms and appropriate responses.

Workplace conversations need balance between transparency and professionalism. Focus on practical accommodations rather than detailed medical explanations. Phrases like “I have a medical condition requiring frequent bathroom breaks and increased water intake” usually suffice for most professional interactions.

Connect with online communities and support groups specifically for diabetes insipidus. These networks provide practical tips, emotional support, and advocacy resources that general diabetes groups might not address. Social media platforms often host active communities sharing real-world management strategies.

Consider wearing a medical alert bracelet or keeping medical identification cards in your wallet. During emergencies when you can’t communicate, these tools inform first responders about your condition and medication needs, potentially preventing inappropriate treatment that could worsen your situation.

Your brain’s thirst signals can sometimes go haywire, leaving you feeling constantly parched even when your body has plenty of water. Diabetes insipidus stands apart from regular diabetes, causing your kidneys to struggle with water balance and triggering that persistent feeling of dehydration. The four main types each have their own triggers, from brain injuries to genetic factors, but the good news is that early detection makes all the difference in getting your life back on track.

Don’t ignore those warning signs your body is sending you. If you’re drinking gallons of water daily and still feeling thirsty, or if you’re making frequent trips to the bathroom, it’s time to talk to your doctor. Modern diagnostic tools can pinpoint exactly what’s happening, and today’s treatment options are more effective than ever. With the right management plan, you can take control of your symptoms and live the full, active life you deserve.